Let’s Hear It for the Supremes!

GPS trackers are a form of search, and police must obtain a search warrant to use them, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled. This comes as a setback to government and police agencies who increasingly rely on GPS surveillance. Justice Scalia said the government’s installation of a GPS device to monitor a vehicle’s movements constitutes a search and violates the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable search and seizure.

The most interesting part of the Supreme Court decision pops up in a somewhat open-ended what-if comment concerning future issues that at least one justice thinks the court should address. Consumer privacy issues remain very much alive and potentially troublesome for location-based services in the United States

Justice Samuel Alito said the court should examine how expectations of privacy affect whether warrants are required for remote surveillance using electronic methods that do not require the police to install equipment, such as GPS tracking of mobile telephones. “If long-term monitoring can be accomplished without committing a technical trespass — suppose for example, that the federal government required or persuaded auto manufacturers to include a GPS tracking device in every car — the court’s theory would provide no protection,” Alito wrote.

This, or its exact counterpart, has already occurred in cell phones: government-mandated location technology embedded in all devices, over a sliding timescale that comes to maturity, or full application, fairly soon.

The Register-Guard newspaper of Eugene, Oregon, published an editorial containing the quote reprinted in the introduction to this column. The writer went on to say that “The result was a ruling that sidestepped tough questions, such as how to treat information held by cell phone companies and how to treat information gathered from devices that are installed at the factory.”

The Register-Guard went on to state “Advances in science and technology have produced GPS devices that have unlimited potential for abuse.”

“In the face of the very real threat of ubiquitous surveillance, Congress should complete its revamping of the federal Electronic Communications Privacy Act. Lawmakers have begun work on this task, but the legislation is not ready for passage.”

The words “no protection” in Justice Alito’s opinion imply that personal cell-phone records are open season to government investigators. Such has already been the case in a number of instances.

Murkier than government use — if such a concept is conceivable — is commercial use of a consumer’s location data. In other words, privacy. This issue has been raised since GPS-enabled phones were first theorized, and since the very whisper of the first location-based service, but it has never been fully or adequately addressed by anyone in industry or government. The notion of “granting permission” to use one’s location data, in order to benefit from services thus provided, still seems unresolved to me.

Most consumers and cell-phone users do not have a clear picture of just how far the ball goes if they check a box that says “agree to terms” or otherwise signify that they are releasing their location data in some undefined form. Sure, they think they’ll just get a coupon the next time they pass near an industrial-strength coffee shop. They have no idea just how much their location data and travel patterns could be exploited by companies seeking to sell them something based on their profile. If you think robotelemarketing – the automated sales calls, often extremely deceptive in their offer, that come as you’re sitting down to dinner – are the worst form of pest, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

The Eugene Register-Guard made this recommendation: ““In the face of the very real threat of ubiquitous surveillance, Congress should complete its revamping of the federal Electronic Communications Privacy Act. Lawmakers have begun work on this task, but the legislation is not ready for passage.”

I am not intimately familiar with the draft of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, but I have a feeling it does little more than scratch the surface on this issue; it probably focuses on government use of private citizens’ location data, and does not begin to consider commercial use.

So far, we are just talking about the United States.

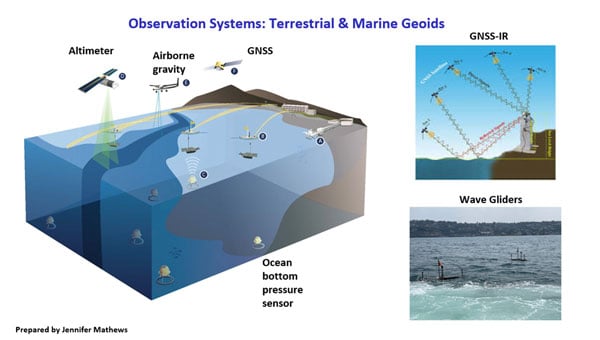

Regarding GNSS use elsewhere around the world for tracking criminals:

In Russia and China, one can reasonably presume that the interests of the state will crush any notion of citizen rights, so that government and police use of GNSS tracking will be placed under no restriction. Europe under the European Union has fairly strong citizen protections in some areas, less so in others. Japan, Korea, Australia . . . I just don’t know.

Regarding GNSS use elsewhere around the world for tracking ordinary citizens’ location and travel patterns for commercial — that is, sales and marketing — purposes, I must again claim ignorance regarding the established ground rules in these countries, if there are any.

Anywhere in the world, if GNSS should be perceived as a tool of Big Brother (government) or Big Broker (industry selling and buying consumer location data), then all navigation systems acquire a big PR problem, which translates into big funding and modernization problems. That outcome, that uncertainty, would affect everyone in or associated with GNSS provision. So we all have an interest in seeing, or making, or shaping, some resolution.

Presumably, we are all waiting around for a test case on privacy versus commercial interests. With the location-based services (LBS) market poised — same as it ever was — on the brink of widespread acceptance, it might benefit everyone if such a case came sooner rather than later. Or if the U.S. Congress tackled the issue before being required to do so by the courts.

Follow Us