European geolocation standard to certify mobility solutions

By Xavier Leblan and Giuseppe Rotondo, GUIDE-GNSS, Toulouse, France

Miguel Ortiz, Université Gustave Eiffel, Nantes, France

and Christelle Dulery,CNES (French Space Agency), Toulouse, France

Geolocation errors, degraded signal and environmental masking

In a perfect world, the positions calculated by trilateration using the signals transmitted by GNSS satellites would always be accurate to within a few centimeters. Unfortunately, in addition to the intrinsic quality of the receivers, many factors alter the measurements made by a GNSS receiver and degrade the final geolocation data.

To begin with, the GNSS system itself suffers from multiple imperfections including so-called “global” errors. For this reason, the satellite navigation system is complemented with the broadcasting of assistance messages to increase the performance of receivers compatible with SBAS systems, such as EGNOS for the European continent.

In addition, for terrestrial applications, the satellite signals are affected by several phenomena caused by the immediate surroundings of the receiving antenna. These are the so-called “local” errors, such as terrain, bridges, infrastructures, vegetation and interference of any type. Depending on the areas covered, the trajectories calculated by the terminals deviate more or less from that actually taken by the vehicle (antenna), i.e. the “reference trajectory,” also called “ground truth.”

Sources of error in urban geolocation include:

Global errors

- Orbits and clocks

- Satellite geometries

- Ionosphere, troposphere

Local errors

- Obstruction, attenuation

- Multipath and diffraction

- Interference, jamming, spoofing

Terminal errors

- Receiving chain

- Algorithms and services

- Navigation sensors

Classification of position errors

To study those phenomena having the greatest impact and likely to be the most frequent, the different types of errors are displayed as a risk matrix. As the “global” errors can be considered to be handled by the regional SBAS system, the pre-eminence of the so-called “local” errors should be addressed.

Description of the main sources of local errors

To observe the effects of local phenomena on the propagation of signals, a dozen identical receivers — with the same configuration and sharing the same antenna — were mounted on a vehicle and driven through urban and peri-urban areas.

We focus on four particularly impacting phenomena to visualize the trajectories calculated by the receivers.

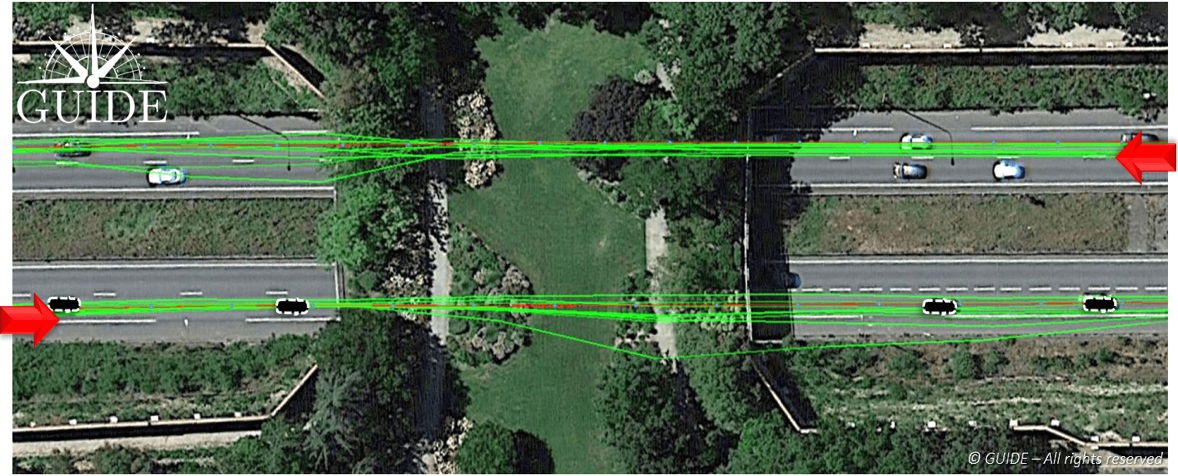

Positioning errors due to bridges

In the picture, below, the test vehicle passes under a bridge in both directions. In both cases, the trajectories diverge under the bridge and converge further on. Here it is easy to understand the shortcomings of results based on a single pass, in other words based on a single measurement.

Positioning errors due to vegetation

In the image below, the test vehicle is on an avenue lined by trees whose branches and canopy cover the road. The foliage attenuates and, more importantly, diffracts the radio waves arriving from the satellites, thus degrading signal reception. This results in dispersed trajectories. Each receiver provides a different measurement. Note that due to the proximity of buildings, the center of the position distribution, in the presence of multipath, deviates slightly from the reference trajectory.

Figure 4. Effect of diffraction of GNSS signals on receivers passing under tree canopies. (Image: Authors)

Positioning errors due to buildings

In the composite image (in order to show the main building) below, all the receiver trajectories are deviated towards the building alongside the avenue. The situation highlights the consequences of a phenomenon called “multipath.” When a receiver captures reflected waves, the signal propagation time — used to calculate the pseudoranges — is increased and the accuracy of the end position is degraded. This effect is well known and easily observable during static measurements.

Positioning errors due to interferences

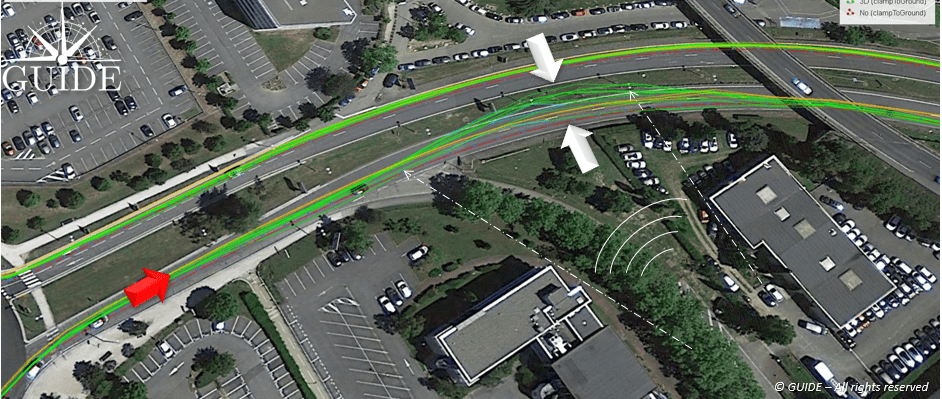

In the image below, the on-board receivers have been disturbed by “transitory” interference. On the outward journey, twenty minutes earlier, no problem had been detected for the trajectories on the other side of the expressway.

On the return journey, this unidentified interference degrades the accuracy of the receivers with a visible dispersion of the trajectories. In other situations, intentional or unintentional interference could completely block out the GNSS band preventing any position measurement.

In this case, the source of the interference seems to come from the bottom right, guided by the two parallel buildings.

Figure 6. Effect of unidentified temporary interference on signals for GNSS receiver. (Image: Authors)

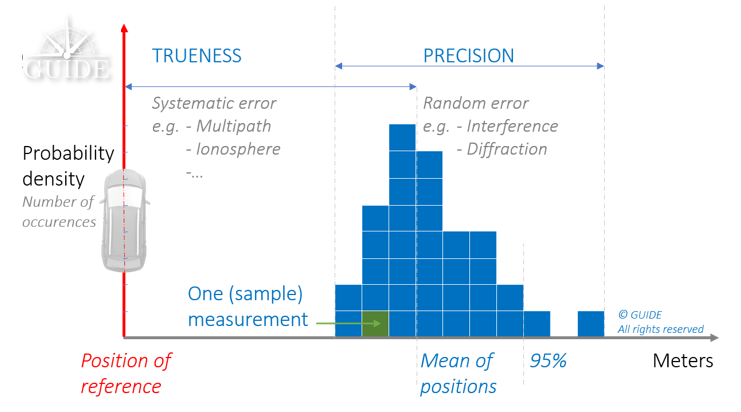

Trueness and precision of position measurements

Receivers of the same batch behave differently depending on the environment. For a predominantly multipath situation, they all converge to the same wrong position. On the other hand, when the propagation phenomena become more complex with multiple diffractions, such as reception under foliage, each receiver produces a position with a different error. For complex environments, we have a combination of these two behaviors.

The first behavior is deterministic. Metrology uses the term measurement “trueness,” which stands for “closeness of agreement between the average of an infinite number of replicated measured values and a reference value.”

The second behavior is non-deterministic. In this case, metrology uses the term measurement “precision,” which stands for “closeness of agreement between indications or measured values obtained by replicated measurements on the same or similar objects under specified conditions.”

Terrestrial applications often offer a varied mix of environments where “trueness” and “precision” errors accumulate. It is essential to consider both components in order to characterize and study GNSS receiver performance.

Statistic distribution of the different positioning errors:

Figure 8. A single position measurement at a point has two unknowns: The weight of deterministic (trueness) errors compared to those that are not (precision). (Image: Authors)

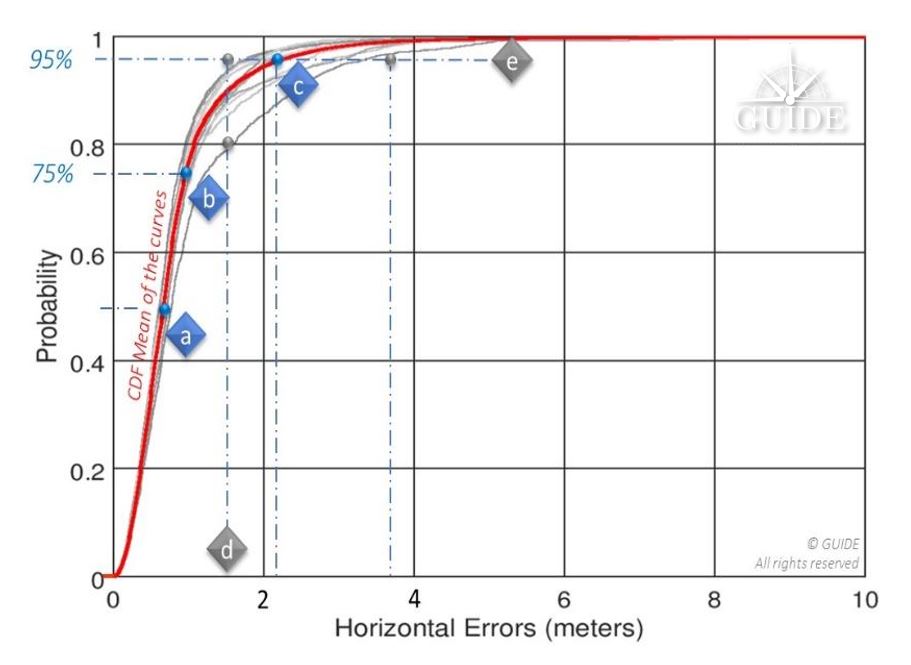

Figure 9. Statistical distributions of errors for a trajectory (scenario), that is the percentage of all errors (probability) lying beneath a given accuracy level. (Image: Authors)

Above, 95% of the positions calculated during a replay have an accuracy better than 1.5m; this same value is only reached with ~80% of the positions calculated during another replay — see vertical line [d]. The horizontal line [e] illustrates the spread of the horizontal position by considering 95% of the positions of two replays: for one the displayed accuracy is ~ 1.5m and for the other it is degraded to 3.5 m. This curve will always point to the same reference points [a], [b] and [c] recommended by the standard EN16803-1 and corresponds to the percentage of measurements respectively less than 50%, 75% and 95%.

By way of example, the evaluation of a single receiver on board a vehicle travelling in an urban environment does not allow separation of these two components. Indeed, signal degradation determines the degree of dispersion of the “random” component of the measurements. Thus, in certain environments, each additional receiver will produce a different result. However, the analyses of a single onsite campaign relies on just one single sample (single trajectory of the terminal under test), where a panel of measurements is essential. In fact, the available statistics prove insufficient to characterize a receiver, even at the cost of doing long runs.

Figure 10. Visualization of the combined deterministic and non-deterministic errors. (Image: Authors)

Live testing is therefore rather intended for final integration.

On the other hand, a constellation generator will synthesize ideal signals derived from mathematical models, and, in any case, not representative of the real environment. The measurements will then only be deterministic, that is, subject to “systematic” errors. Repeated simulations on the same receiver will always produce the same measurements. Nevertheless, this type of test bench offers many advantages for simulating unobservable situations in the real world.

Disparities in analysis possibilities on position errors based on:

Figure 11. Typical results for repeated measurements obtained, respectively from left to right,

with synthetic signals and real-world signals. (Image: Authors)

In summary, the main error profiles are described below.

Each situation combines both trueness and precision errors. This latter component requires several runs in the same configuration to determine the potential measurement spread.

Figure 12. Position error profiles (measured trajectories/DUT) depending on the environment. (Image: Authors)

What is GNSS metrology?

As a first approach, characterization of GNSS performance would require many receivers on the same test vehicle. This method is certainly useful in the experimental stage, especially to understand the impact of propagation phenomena on positioning errors. However, it has major disadvantages, both from a logistics point of view and because of the basic metrological requirements.

To obtain reliable and useful measurements, from an operational point of view, the tests must be “representative” of the areas to be covered and “reproducible” to check the results and make valid comparisons, for example, between two receivers, two firmwares, two settings, two antennas and even two hybridizations.

Under these conditions, replay techniques, often referred to as “record and replay,” meet the expected requirements. For the record, this metrology method consists in digitizing the GNSS signals received by the antenna on board the definition vehicle, taking care to collect all the data associated with the tests (VIDEO, INS, DMI, NRTK, …), above all, the ground truth. Thus, at the end of the campaign the GNSS signals and other data are synchronized and restored on a replay bench consisting of an “SDR replayer.”

Replaying the same scenario on a receiver makes it possible to reproduce the recording conditions identically. Each pass generates new measurements, equivalent to using an additional unit, virtually onboard. Compiling the results thus highlights the non-deterministic errors, that is, those which by their random nature emerge from the others.

Test laboratories such as GNSS GUIDE design and market test data that can be replayed directly on the main simulation instruments capable of operating in two modes: simulation and replay. The replay configurations are generally much more affordable than the larger, structurally more complex constellation generators. In addition, the implementation of replay sessions is simple, fast and requires no special training.

In addition to scenarios made on request, the available libraries already cover a multitude of cases, previously inaccessible for an isolated user. They open up the possibility of testing terminals in different latitudes with varied terrain and neighborhoods composed of typical architectures.

Conclusion

The French Space Agency (CNES) has financed several R & D contracts for the development and validation of this replay technique (record and replay). It is already recommended by CEN / CENELEC through the series of EN16803 standards to characterize and classify the performance of GNSS terminals. This methodology complies with the basic principles of metrology.

The test conditions are reproducible and representative of operational conditions. The measurements are repeatable and allow separating the systematic errors (trueness) from the random errors (precision). Measurement uncertainties are also accurately established.

During an on-site measurement campaign, the statistical distributions of two identical receivers on board the same vehicle lead to different results. Thus, no characterization can be established at this stage.

With a replay bench, after several iterations of the same scenario, the average values of the measurements on a CDF tend toward a curve characterizing the performance for that scenario.

Instrumentation dedicated to replay operations is less complex and less expensive. Statistical models of simulations are replaced by scenarios of GNSS signals previously digitized in the field or on constellation generators. Thus, whether they come from a real or synthetic environment, these GNSS signals are easily restored, while drastically reducing the preparation and execution times. The economic benefits of this test technique are now evident and are favoring its adoption by the transportation industries.

References

- Niels Joubert, Tyler G.R. Reid, and Fergus Noble (2020), Developments in Modern GNSS and Its Impact on Autonomous Vehicle Architectures

- Andrej Tern and Anton Kos (2018), Positioning Performance Assessment of Geodetic, Automotive, and Smartphone GNSS Receivers in Standardized Road Scenarios

- Ni Zhu, Juliette Marais, David Betaille, Marion Berbineau (2018), GNSS Position Integrity in Urban Environments

- C. Rouch, B. Bonhoure, F.X. Marmet, T. Chapuis, H. Secretan, V. Bienfait, X. Leblan (2016), Measurement campaigns and PVT experiments with new Galileo satellites

- B. Calvet, L. Montoya, P. Grandjean, X. Leblan (2015), The GUIDE High-Precision test facility (GNSS laboratory)

- G. Duchâteau, X. Leblan, Y. Capelle, W. Vigneau and F. Peyret (2014), Certification of Road User Charging: Approach, standardization and role of laboratories

Follow Us